»There is no Eden of the Wild«

An interview with Catherine Bush at the Climate Cultures Festival Nov. 2021 in Berlin

- Part 2: Climate Responsive Thinking -

Interviewer: Sieglinde Geisel and Martin Zähringer

- And do we need labels like climate fiction?

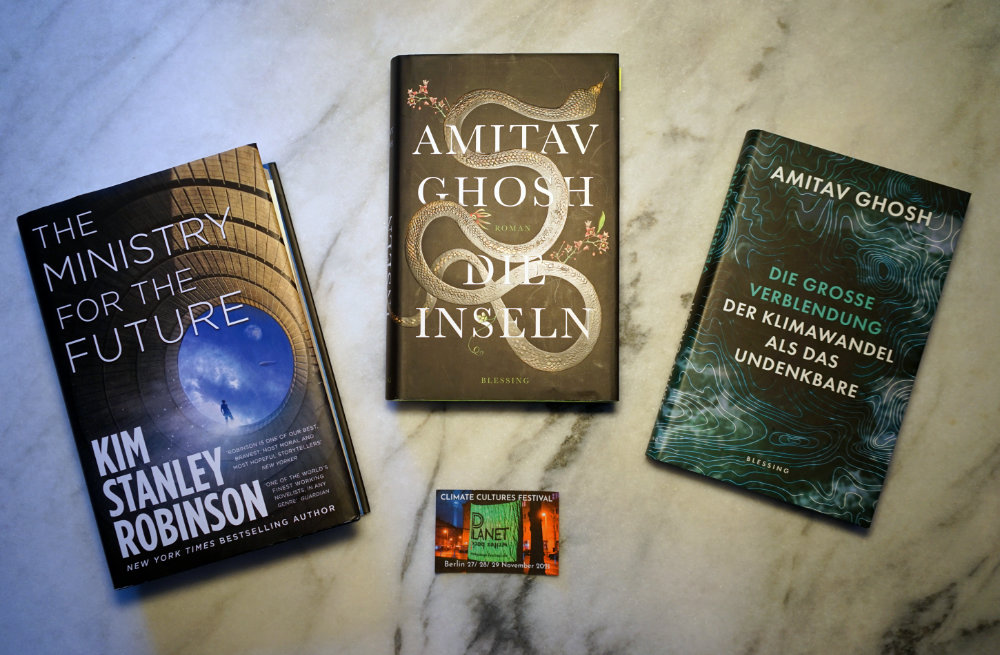

I think that labels can be useful in some contexts by calling attention to the importance of art responding to the climate, in the same way that your Climate Cultures Festival does. Offering that focus is important. And saying to the world, yes, we need to think about this. We need to create art that responds in some way. Climate fiction is a new kind of realism. Kim Stanley Robinson was talking about that, too.

The way we can respond as artists is so various, there's no one way. And it may not even be exactly about the climate, we can still bring the energy of what the English Nigerian novelist Ben Okri has described as our existential creativity. What is it necessary to talk about at this moment of crisis? Because it is a crisis.

Catherine Bush

- Catherine Bush is a Canadian writer of fiction and essays. She teaches creative writing at the University of Guelph. In 2019, she was a Fiction meets Science Fellow (FMS) in Germany, a research project that aims to combine science, fiction, and art. She is a member of the international network Climate Fiction Writers League.

- Her latest novel, "Blaze Island", was puplished in 2020 by Goose Lane Editions. It is about an outcast climate scientist who wants to escape his history on a windy island on the north coast of Canada.

- In 2021 she visited Berlin as a guest at the Climate Cultures Festival where this interview was made.

↗Catherine Bush

↗Blaze Island - Gose Lane Editions

↗Climate Fiction Writers League

- What is going on in Canada with climate-responsive fiction?

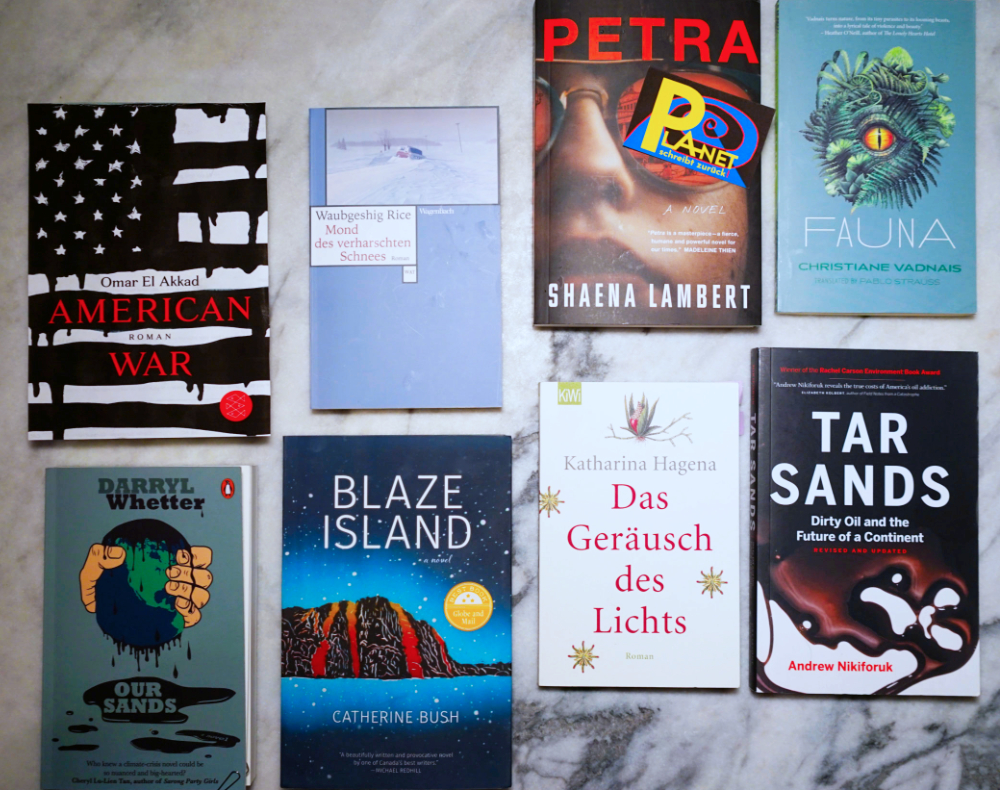

At the festival you had the indigenous writer Waubgeshig Rice, the author of "The Moon of Crusted Snow". His work might not look obviously like climate fiction, but it is. As he said at the festival, North American indigenous people have been facing crisis --- both genocide and a land crisis, land stolen and degraded as part of ongoing colonial and industrial expansion -- for generations.

There's speculative work being done by indigenous writers in Canada that certainly confronts the biodiversity crisis and the larger social breakdown that might arise because of a climate crisis. That's very important work.

- Can you name some of these writers?

There's a young Quebecois writer, Christiane Vadnais, who is writing really interesting, hallucinatory short stories of a climate-disturbed world, in a collection called "Fauna".

And, from British Columbia, there's a wonderful writer named Shaena Lambert, whose most recent novel, Petra, is about Petra Kelly, the German Green Party's Petra Kelly. Although it's set in the `80s and `90s in Germany, it brings a contemporary focus, making us see how things that Petra was calling attention to, and her awareness of our deep interconnectedness, resonate in a climate-conscious fashion today.

There's one oil sands novel that I know of, "Our Sands", by Darryl Whetter. I can think of some fascinating speculative novels by racialized writers including Catherine Hernandez, Larissa Lai and Premee Mohamed that describe a world in the wake of climate and social collapse.

- What can you say about the academic engagement?

I'm involved in a project called ↗Imagining Climates – hosted by the Guelph Institute of Environmental Research at the University of Guelph – where we're trying to create a multidisciplinary site not just for writers, but researchers in different disciplines to come together and have conversations about the imaginative possibilities of climate thinking and the necessity of imagination across disciplines for thinking our way into the future.

One of our sub-projects is something called Microclimate Stories. We commissioned a series of 150 word stories from both writers and scientists. Super short. But it's really fantastic what people can do in such a short space, speaking to a diversity of climate experiences.

»And so that is a climate-responsive novel because it's not ignoring the fact of the climate crisis even though it's not addressing it directly.«

- Why do you think that so many writers are not climate responsive in their writing?

I think it takes time and also it depends how you define climate writing. You could call a refugee novel like Omar El Akkad's "What Strange Paradise" a climate novel, given that the climate crisis will certainly amplify the refugee crisis. El Akkad himself has written about that.

There's another Canadian novel that I love, which again has a German character in it. "The Search for Heinrich Schlögel" by Martha Baillie. I don't know if it's been published here, but it's about a German man fascinated by the Canadian North, who sets off on a trek across Baffin Island in the 1980s and goes through a time warp and arrives in Pagnirtung in the year 2000.

And so that is a climate-responsive novel because it's not ignoring the fact of the climate crisis even though it's not addressing it directly.

It's speculative, and it's really about the estranging encounter between cultures, not directly about climate change. But the character develops a form of tinnitus in his ear. He can't get rid of the sound of melting glacial water. And I find that detail such a resonant and powerful way of alluding to the climate crisis.

»Climate fiction is a new kind of realism. Kim Stanley Robinson was talking about that, too.«

- Would you call that novel climate fiction?

I don't know. But the climate crisis is nevertheless present. And so that is a climate-responsive novel because it's not ignoring the fact of the climate crisis even though it's not addressing it directly. I've never forgotten that element. I feel like the imaginary tinnitus passes into me and it's now in my ears and becomes a sound I can't lose either.

»To be human is to be part of nature. The human/nature separation is a false one.«

- What does Nature Writing mean to you in these times of climate change?

To be human is to be part of nature. The human/nature separation is a false one. And if you're writing about plastics and the disintegration of plastic in the environment, in the human body, that's nature writing. It may not look like old-school nature writing, but it's contemporary nature writing.

A Canadian writer, David Huebert, who has written some fantastic climate-themed short stories, including a dream-like story set in the oil fields of southern Ontario, describes himself as a dirty nature writer.

- Dirty Nature Writing? Yeah, that's a good term.

I have an essay called "Invasives" in the online American ecological spiritual magazine, Emergence. It's about my relationship as a child of immigrants, whose parents were part of the huge immigrant invasion to North America, to invasive plant species in my home environments.

I live between city and country. I have a little place two hours outside of Toronto, in southern Ontario. And it's a little heaven in some ways. But the land is full of invasive plants, including one brought over by European settlers called wild parsnip that will burn you, even scar your skin if you get the sap on you.

If you get it in your eyes, it can blind you. You can also eat the root which is why settlers brought it. So I'm in my little enclave with my native plants planted to draw bees and insects, which they do, in the midst of fields farmed industrially, sprayed with glyphosate and other chemicals, surrounded by a lot of invasive species. There's another wild grass spreading widely all over southern Ontario called European Phragmites. It grows five metres tall and 80 percent of its biomass is underground, and it completely takes over wetlands. For better or worse, all this is nature.

»We do need to love the damaged world but that doesn't mean we don't have to take action.«

- What is the tone of your "Invasives"?

There is no Eden of the wild. Even in the far North, the permafrost is melting- the legacies of industrialism are on the land. There's no way back. We need to love this damaged world. Acts of repair and regeneration are possible but no return to some untouched wilderness.

But if you tell the Fridays for Future, you have to love the damage. I would think they could not understand this - really love the damage? We do need to love the damaged world but that doesn't mean we don't have to take action.

- Do you think that they wouldn't appreciate that sentiment?

I would answer with a Buddhist sentence: You can only change what you accept. Accepting is not yet loving, but acknowledging and noticing what's there, and where you are, is crucial. Then you can start to love and to change things. We can't deny the damage and we can't go back, we can only move forward.

»How can we narrate from places outside the human, both in fiction and nonfiction, bringing awareness to other forms of consciousness?«

- And how do we figure out how to do that?

In North America, we can't go back to what North America was before the Europeans and other waves of immigrants came, sadly, even if we feel nostalgic for what has been lost. We have to figure out a way to go forward on this land altogether. Those of us who are newer arrivals must discover some way of loving land that isn't historically ours and caring for it.

We talk so much about decolonisation these days, but we tend to think only about humans, that we should not colonize other peoples, but we also have to decolonize our mind towards nature so that we're not colonizing nature.

Yes. We need to recognize how dependent we are on insects, for instance. We don't tend to think about how, as humans, we really need insects to survive. We're dependent on bees. And we have intimate relationships with bacteria.

I think we should learn to talk more about the relations, not because we as humans need the insects. Nature needs the insects to survive. We always think from this subjective way of thinking. How can we change these perspectives in literature - maybe to get to a more planetary way of thinking or consciousness?

How can we narrate from places outside the human, both in fiction and nonfiction, bringing awareness to other forms of consciousness? There's a really interesting queer Black American nature writer, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, who's investigating her relationship to marine mammals, in a beautiful series of essays. She speaks to our need to listen to other beings, to cultivate a deep listening practice. Certainly in terms of my own writing,

I hope in my next novel to make more space for more-than-human consciousness. I'm still trying to figure out how. But that seems an essential part of planetary thinking.

»There's a wealth of refugee literature, and we don't always think of that as climate fiction, but in a sense it is climate fiction.«

- The planet is turning around itself. But in which direction should literature move?

The challenge is also taking us back to older forms of storytelling. In fairy tales, in folk tales no matter the culture, we had talking animals and talking plants. The world was much more animate. So that desire to have a living world in fiction and recreate it in new ways brings us into renewed relationship with older kinds of stories, too. Amitav Ghosh does this in his novel "Gun Island", and speaks of these other stories with other belief systems being introduced by climate refugees.

There's a wealth of refugee literature, and we don't always think of that as climate fiction, but in a sense it is climate fiction. So much of the contemporary refugee crisis is caused by climate problems, problems of drought and the destabilization of land that then lead to crisis over resources. So refugee literature blurs into climate literature.

For me the real question is how can we bring an awareness of climate disturbance to the page. If we're writing a love story set in Berlin, how do we bring that awareness of the floods or a gale or some strange weather phenomena happening somewhere, perhaps not far away, to our daily lives? Or thinking about the way we're permeated by plastic or that we don't hear the song of house sparrows anymore.

All those small details are what make up this big change. How can we keep that awareness alive imaginatively? That seems to me the project, rather than feeling that every work of fiction has to be about the climate crisis.

And if you're writing realism that acts as though none of this is happening, that's a kind of dangerous denial. Not denying that this is the substance of our current reality seems really important. Again, it doesn't mean everyone has to write a novel about the climate crisis, but bring some awareness to the page, even in a realist novel of daily life, even if it's about people who are denying the realities in which we live.

In Canada, the western part of the country just had flood after flood the last few weeks. The eastern part also went through huge floods. There was wildfire smoke in Toronto this summer. So these climatic experiences are there. And if you're writing realism that acts as though none of this is happening, that's a kind of dangerous denial.

»Your festival is doing essential things to spark connections between writers and begin conversations and inviting us to imagine in new ways.«

- You know what I see in adult literature, especially in Germany, people are still writing what they always did. They're writing about their childhood, about their divorce and about their Nazi great-grandparents??. Of course, you can do that very well without any climate change. And so that kind of business as usual goes on in the literature even more than in the economy and in politics. Is there any hope?

Speaking about the need for planetary conversations, I just want to say thank you for the Climate Cultures Festival for bringing us together. Certainly this was an international conversation and an opportunity for me as a Canadian writer to find myself in conversation with Minik Rosing from Greenland and Katharina Hagena who's writing about the Canadian tar sands.

To come here and be in conversation with indigenous Anishinaabe writer Waubgeshig Rice was a great honor for me. Your festival is doing essential things to spark connections between writers and begin conversations and inviting us to imagine in new ways.

For instance, I've thought quite a bit about ice but hadn't thought as much about petro-culture. Your invitation for us to think not just about climate fiction or climate literature but climate culture is such a necessary one -- culture in the broadest, most interdisciplinary way. I would want to add that climate education and climate pedagogy are also really important.

As someone who teaches in a university, I'm spending a lot of energy thinking about this. How do I bring climate awareness to the classroom, as a writer but also as someone who teaches literature and wants to engage in cross-disciplinary conversations with scientists and social scientists? At all levels of education, from primary schools into universities, climate thinking has to suffuse every discipline and we have to figure out how to do that. That's an essential part of radically changing our cultural story and reimagining the future.

Thank you.