»There is no Eden of the Wild«

An interview with Catherine Bush about climate-responsive thinking at the Climate Cultures Festival Nov. 2021 in Berlin

- Part 1 -

Interviewer: Sieglinde Geisel and Martin Zähringer

S.G.: As far as I know, "Blaze Island" is the first of your novels that deals with climate change. Is that right?

C.B.: "Blaze Island" is my fifth novel. My first, "Minus Time", doesn't deal with climate change but it has a strong ecological thread. It's about a woman who becomes an astronaut whose daughter gets involved with a gang of animal rights activists. While the mother is up in space, the daughter is very much committed to saving life on Earth. So I've had strong ecological interests for a long time. It wasn't that all of a sudden I started thinking about climate issues. I’ve also long been drawn to complex moral quandaries.

In "The Great Derangement", Amitav Ghosh calls out literary writers, saying they need to be responding to the climate crisis in their work. I'd already been working on "Blaze Island" for a few years when I read that.

Catherine Bush

- Catherine Bush is a Canadian writer of fiction and essays. She teaches creative writing at the University of Guelph. In 2019, she was a Fiction meets Science Fellow (FMS) in Germany, a research project that aims to combine science, fiction, and art. She is a member of the international network Climate Fiction Writers League.

- Her latest novel, "Blaze Island", was puplished in 2020 by Goose Lane Editions. It is about an outcast climate scientist who wants to escape his history on a windy island on the north coast of Canada.

- In 2021 she visited Berlin as a guest at the Climate Cultures Festival where this interview was made.

↗Catherine Bush

↗Blaze Island - Goose Lane Editions

↗Climate Fiction Writers League

M.Z.: Hasn't there been some inspiration from Shakespeare too?

The original inspiration for the novel was seeing a production of "The Tempest" at the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-on-Avon in the UK back in 2006. The production stuck in my mind because it was set in the Arctic, on an Arctic island. It wasn't about climate change, but the Arctic environment really struck me. I began to think about how I might turn Prospero, the magician in Shakespeare's "The Tempest", into a contemporary climate scientist drawn to manipulating the weather. So it's been a long gestation.

»I like to think about my writing as what I call climate-responsive thinking.«

- Do you feel it is your duty as an author now to tackle the subject of climate change and fiction?

I don't know that I would phrase it as a duty. You can't write from a place of duty and create art that has imaginative life. You have to write from a place of desire. I do feel it as a call, as an imperative. I like to think about my writing as what I call climate-responsive thinking. It's really important to bring my existential awareness of the climate crisis to the page whenever I write, which is different than feeling must, always, write about the climate crisis. But I must write with an awareness of rising carbon levels and rising sea levels and melting sea ice and all the ways in which our lives are implicated in petro-culture.

I'm really astonished how oblivious so much current literature is to that when I feel the climate anxiety grounds my being so deeply. I wrote an essay about this called "Writing The Real", which came out in Canada. It's challenging to know how to write in response to the climate crisis, because even now the crisis remains quite abstract for many. So the question is, how do you do this with specificity, in a way that has narrative life and that's not so depressing or dystopic that people go, I don't want to hear this.

- How did you write with that awareness in "Blaze Island"?

I wanted to write about the climate crisis directly by focusing on a climate scientist, Milan Wells, and his daughter, Miranda. I hadn't seen many climate scientists in fiction and I was drawn to the dilemma of being both a climate scientist and a parent: When, as a climate scientist, you know so much about what disasters may lie ahead, what might the desire to protect your child from a disintegrating world lead you to do? How do you hold that knowledge alongside your emotions of fear and love for your child and your desire to protect your child? And as the scientist’s daughter: How do you live with your father's fear and grief, which you can feel but also don't want to think about, because you want to have a childhood, you want to be in the world?

How do you live in this wild place, on this remote island, where the wind presses against you like another body and all the elements are a living world that you inhabit?

- Isn't it quite a conventional psychological novel?

Climate change as a phrase is kind of a cliché, especially when you put it in fiction. People bring all this baggage and expectations to the words and turn off too easily. So it was a literary challenge: How do you write a novel that addresses climate change without using the term climate? Especially since we don't actually experience climate. Climate is an abstract term for aggregates of weather. Over time, we experience weather. So, yes, it's a psychological novel, but what I also wanted to have on the page is this experience of wind and rain and ferocious storms and sea ice coming in and icebergs coming down the Labrador current. How do you live in this wild place, on this remote island, where the wind presses against you like another body and all the elements are a living world that you inhabit?

- When you say that writing about climate change is a call for you. What's your goal?

I want to bring people's attention to the large issue of our changing climate, which is a crisis that asks us all to change our lives and the deep cultural narrative in which we're living. We need to radically transform and think beyond narratives of comfort and economic growth. A novel can bring us inside the bodies of characters.I think that's what a novel can do. We need to encounter acts of imagination about our current world.

We're all called upon to imagine a new future and to my mind that requires us to engage with the world beyond the human, because the climate crisis is so tied to the crisis of the biosphere. We need to look to our kin who are more-than-human and we need to approach the whole living world beyond us with greater attention. We need to love the world before we can transform ourselves in order to transform it.

»In a sense, Frank is becoming a little bit iceberg. Asked to swallow a sliver of iceberg ice, he does, and part of the iceberg is now inside him.«

- What could be the specific role of a novel in that?

A novel is a way of asking people to pay deep attention to the world by calling us to notice things on the page that we might fail to notice in life -- and notice through feelings and bodies. So, in "Blaze Island", I hope that people will walk with Miranda on the island, along the rocky paths of the shore. She goes foraging for berries and pays close attention to the wind.

The novel opens in the aftermath of a huge hurricane. There's no power on the island. Everyone has to adapt. I want to dramatize how people respond to change, sudden and slow.

On the island, there's an immediate danger and in the wake of that, strangers appear. Frank, a young man, is one of them. He will burst this protective bubble in which Miranda has been living and force her to confront the larger world, which is already in the midst of the slow, seismic changes of the climate crisis. Meanwhile she is showing him, and through him the reader, this island and its wonders, teaching him about the natural world, about ice.

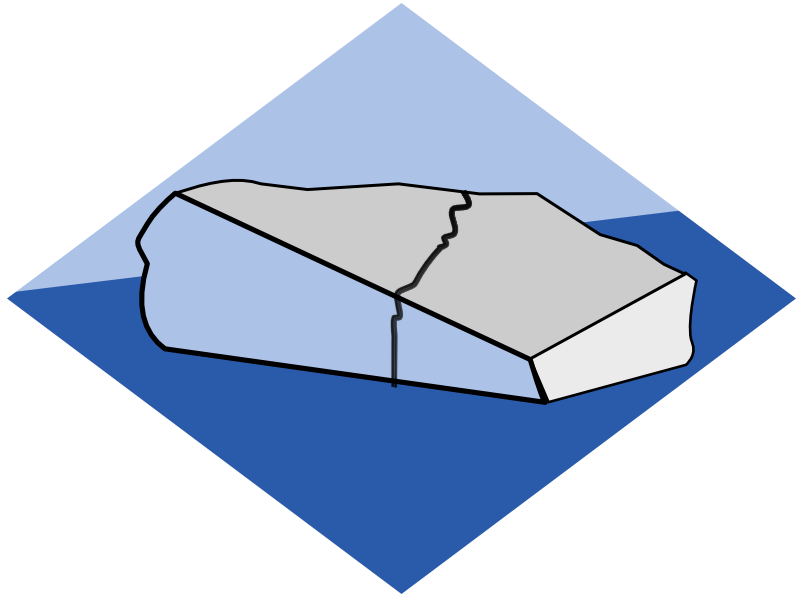

In a sense, Frank is becoming a little bit iceberg. Asked to swallow a sliver of iceberg ice, he does, and part of the iceberg is now inside him. Miranda's father wants Frank to learn to love the ice, love glacial ice – because iceberg ice comes from the Greenland ice sheet – in order to care for it in the way that we all need to care for glacial ice, for our planetary survival.

A novel can bring us inside the bodies of characters. I think that's what a novel can do. We need to encounter acts of imagination about our current world. Ask us to imagine what it's like to drink and swallow glacial ice, even if we don't actually have a chance to do that. I've been lucky enough to do it on Fogo Island, the actual island that inspired "Blaze Island", where people put bits of icebergs in their drinks. I mean, you better not waste it. The ice has come all the way from Greenland, and it's going to melt. So why not put it in your drink?

As a reader there's a deeper act of imagination that's being asked of you. I think that's what a novel can do. We need to encounter acts of imagination about our current world. A novel can allow people to read, see, see things newly, and engage us in loving the world in order to want to save it.

»I very much wanted to think about planet as island, island as planet.«

- Becoming iceberg, yes! Well, we as critics, love conceptional terms like the term "planetary thinking". What do you think about this idea?

I love the idea of planetary thinking. There was that phrase that came up in the Climate Cultures Festival from Frederic Hanusch ➔, who is the exponent of planetary thinking, that we need to think not about being on a planet but being part of a planet. We are part of this planet and in "Blaze Island" the characters are walking out into the world and dissolving their selves as they merge into a landscape of rocks and lichen and caribou.

There's planetary thinking, which we all need to embrace, and also island thinking. I very much wanted to think about planet as island, island as planet. Island cultures have enormous resilience and self-sufficiency, but they also are forced to live within their own limits. It's a bordered world and on this planet we need to think that way too.

We live in a world with limits. When I spent time on Fogo Island -- and I returned there over eight years -- people said to me: In an emergency or a crisis, island people don't despair. They come together as a community and rally to meet the disaster whenever a hurricane comes or a flood and people are cut off without power. And that island thinking, that cheerfulness, that necessary resilience, is an energy that on a planetary scale we need too.

People there acknowledge that climate change is a real phenomenon. I know in other places and other rural cultures, in parts of America or even in Ontario, where I live, in rural communities you might meet people who will deny the reality of climate change. But on Fogo Island, everyone lives so close to the weather. People can tell you every time the wind shifts. Someone will say, Oh, the wind's shifting. I want to bring that knowledge and awareness back to city living so I, too, can feel the wind shifting every time it happens. In my experience no one there would deny that climate change was happening.

- How do they experience it?

Particularly the changes in sea ice. Historically, sea ice came in to shore every year. Sea ice comes down from the Arctic and into the harbors and brings the seals every year. The seals breed on the ice. In recent years, the sea ice doesn't always come in. That's a big difference, and the warming ocean is bringing bigger storms, bringing hurricanes up from the south. That didn't used to happen as much, either. Weather is generally less predictable.

»...we can easily forget how crucial ice, especially polar and glacial ice, is to our planetary survival.«

- What made you choose a place up north in order to write about climate change?

With "Blaze Island" I knew from the beginning that I would use Shakespeare's "The Tempest" as my inspiration. So I needed an island and I've always loved the North. And as I said, I'd seen this production of "The Tempest" set in the Arctic so those ideas came together. Then I needed to find an island where I could spend some time. Fogo Island has a series of artists residencies so there was a practical side. I could go there to stay as an artist-in-residence. But I'm also very drawn to that northern, sub-Arctic climate.

I do feel as someone from southern Canada, from a more southern culture in which we don't have to think or want to think about ice on a daily basis, we can easily forget how crucial ice, especially polar and glacial ice, is to our planetary survival. I've been thinking about ice and about the Inuk writer Sheila Watt-Cloutier's work and her book "The Right to Be Cold", she calls out to those of us who don't live in Arctic climates to think about our responsibility to ice.

- Do you think that literature has the power to change consciousness on a planetary scale?

I think that storytelling can change the way people think. Story by story. Stories invite us to reimagine the world and we can only create a future world that we can imagine. We need to practice this imagining. We need to practice through acts of imagining how to reconnect to a world beyond the human. How we can think of a world beyond capitalism. How we can learn new kinds of resilience. One story alone? Maybe not, but I feel like "Blaze Island" also exists as part of a conversation of climate novels, climate-responsive novels, as a novel among novels.

»Paying attention to the natural world. That kind of noticing can be transformative.«

- Is it also part of a more fact-based conversation about climate change?

Yes, a novel can start conversations and that's been one of the beautiful things about writing "Blaze Island". It's opened up conversations not only about weather and resilience and climate emotions but about climate engineering. This is another theme in the novel: Milan or Alan, the scientist [he changes his name partway through], in order to save his daughter, begins to research and be tempted by solar radiation management. Which is a potential plan to shoot particulate matter into the atmosphere to halt the rise of global temperatures by creating a particulate haze that will bounce back solar rays, which is being researched by actual scientists. It's still in the zone of the speculative, or imaginary, but it is a site of real scientific research.

A novel like "Blaze Island" can get readers thinking about climate engineering in ways that they might not have done before. It's certainly introduced me into conversations about it. People have also said to me after reading "Blaze Island" that they're listening, they're feeling the wind in ways that they haven't before. Paying attention to the natural world. That kind of noticing can be transformative.

And so I think we can create a culture in which imagining is essential, in which imagining the future is essential, and imagining the future not just in dystopic ways. "Blaze Island" is very much not a dystopic novel. It's a novel that's sensual, that I hope creates desire in the reader, a desire to walk back out into the world and care for it. That's what I think novels can do and what we need novels and literature to do at this point in time.